What About The Lazy?

Do They Still Deserve To Eat?

What If They Refuse To Work?

‘What About The Lazy?’ This question seems to come up every time you mention any alternatives to Capitalism, as if it is some sort of ‘gotcha’ question that will render anyone on the Left speechless.

I can’t speak for everyone else, but I’m not afraid to address this subject, and have a lot to say on it. I won’t try and pretend that laziness doesn’t exist1, I won’t deny that laziness isn’t ever potentially a problem, and I admit freely that each of us has the capacity to be lazy. You could call this human nature if you like, but we also have the potential to work very hard.

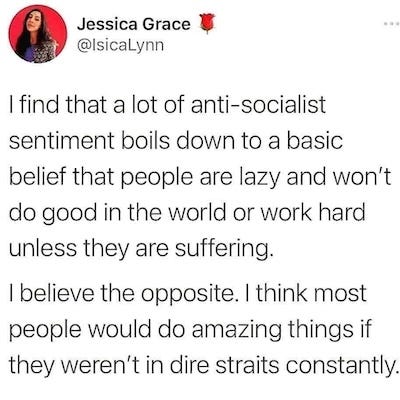

Of course there are lazy people under Capitalism too, so what people are really saying when they ask about the lazy is, ‘How will you motivate people if either a) you don’t offer them money to work, and / or b) you don’t threaten to starve them if they don’t?’ Underlying this is the assumption that people will only work for one of these two reasons.

The Capitalists are right that in our modern society most of us go to work to obtain the things we want, and / or to avoid the risk of hunger and homelessness. The dilemma of the carrot of monetary rewards (and what they can buy) for working, and the stick of not being able to meet our needs by failing to, would indeed seem to be pretty effective for most people, and it isn’t surprising that people presume the world has always operated this way.

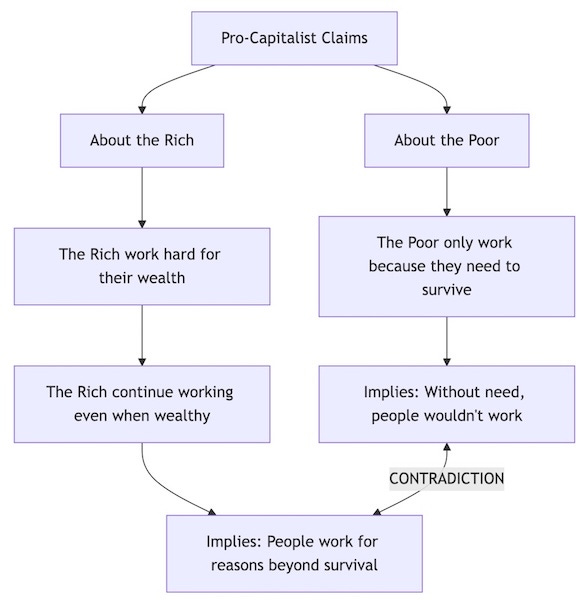

Yet there is an obvious contradiction in this theory, pro-Capitalists also say that the rich work hard to earn their wealth, yet if they are rich they don’t need to, and so therefore wouldn’t be motivated to according to this same reasoning.

But to account for the world before the advent of Capitalism we have to find new theories to explain how humanity was motivated to survive and live and thrive before such incentives existed.

Pre-Capitalist Economics

It can be difficult for people to imagine a different way of doing things, especially when they are so familiar personally with the only way they’ve ever seen it done. However, prior to about three hundred years ago most of the poor rarely used money or expected luxuries, nor did they work as many days as we do today.2

This arrangement definitely had its negatives, unless they were apprenticed to a craftsman or decided to become a wandering minstrel it was likely they’d do the same work their parents were born into, and for most of them that was farming. Those peasant farmers rarely had much of a choice of employer either, as they were born on the lord’s land and would probably die on it.

Even Feudalism was a relatively new system in human history though. We might trace its most rudimentary form to ancient Babylon, when kings arose that demanded an early form of taxation through payment in work or goods-in-kind. It is worth noting that we are focusing on the history of the Middle-Eastern and European models, and such systems were not introduced universally throughout the world, and so parts of it went without such a change for thousands of years.

Prior to this arrangement of subservience to kings, lords and later masters (as managers were originally called), a very different way of organising society existed. Even then people lived in villages, larger settlements, and even cities, often with less rigid structures than came later.

It used to be presumed that most peoples lived in disconnected isolated groups, but now we know from anthropological, archeological and biological evidence that such communities were highly networked and those networks sometimes spanned thousands of miles. Groups like the native Americans made this clear to the Europeans when they had a chance to (in between being slaughtered), but – as it didn’t fit into ‘Western’ theories of the primitive state the natives supposedly lived in – they were often ignored.

If we look at the native American example prior to the arrival of European settlers we see clans that crossed whole continents, and confederacies of tribes as big as countries, which operated co-operatively at both larger and more local levels. There was agriculture and storehouses, but no money, and debt and barter tended to take place between tribes rather than individuals.

So how did they motivate people to farm, build homes, make clothes, and carry out all the other essential tasks without money? It would be easy to presume that people who didn’t work were either prevented from eating or were punished in some other manner, and that this fear of hunger or punishment was the chief motivation before money, but if we look at the evidence we discover that isn’t the case.

The Iroquois Way

Established in the twelfth century (1142 A.D.) the Haudenosaunee Confederacy was formed from five tribes: The Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations, later collectively known as the Iroquois. This largely North-Eastern indigenous alliance has lasted until the present day, and up until the 1500s largely organised themselves co-operatively and peacefully.3

Their villages, often fortified with wooden fences, contained up to 3,000 people. The longhouse homes within could be as large as 200 feet long and 18 feet wide. Land was owned communally within tribes, instead of individually, with each village also having a storehouse administered by the women of the tribe. The early Europeans envied the surplus of food the Iroquois produced, as famines were practically unknown among them.

‘Our Creator gave us our aboriginal lands in trust with very specific rules regarding its uses. We are caretakers of our Mother Earth, not lords of the land.’4

Although they had honourary chiefs they had no firm concept of hierarchy, as one British colonial administrator declared in 1749, they had ‘such absolute notions of liberty that they allow no kind of superiority of one over another, and banish all servitude from their Territories’.5 They had no form of currency or debt, and very little attachment to anything material, yet their lack of material rewards did not seem to have any negative impact upon them.

Without the Puritan work ethic how did the Iroquois organise themselves, and ensure that all the necessary labour was carried out? We know they understood the concept of laziness, passing down stories about lazy animals and the lessons that could be learnt from them.6 However, it doesn’t seem to have been a major issue within their society, so what did they do differently?

Luckily, unlike pre-historic pre-money civilisations, we have contemporary accounts from European visitors which detail how Iroquois society handled work and responsibilities. Although there was a division of labour between the men and women, some of the most responsible positions were carried out by the women, who had their own Council Of Clan mothers, and appointed delegates to the larger clan Council Of Fifty that met to discuss important cross-tribal matters.

These women looked after the storehouses, could redistribute land between the clans if needed, and organised work in the fields. Whatever was harvested or hunted was distributed equally, and there was no mechanism by which one tribes-person could become more wealthy than another. The focus was on the fairness of the work people were asked to do, and avoiding unnecessary labour. As one witness remarked, their collective effort averted ‘every jealousy of one having done more or less work than another.’7

It would be wrong to say that the Iroquois had no incentives, however, as they were brought up with ideals and expectations that undoubtedly would have been a powerful influence upon them, and not living up to those – especially to the point of recklessness, even if uncommon – would have been looked down upon.

Everyone received the same benefits irrespective of their contribution, but there was a strong tradition of autonomous responsibility, they attempted to eliminate any feelings of dependency as early as childhood, when they would have begun to participate in a communal culture, and – although they were taught to think as individuals – their work was seen as being for the good of the community.8

This is but one example of the many pre-money societies within which people shared freely, and thus worked without the incentive of money or the fear of hunger. There are dozens of more examples that you can find in books such as The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow, or on the Anarchy In Action website.

But the lack of currency, property, fear of punishment, or existence of hierarchy doesn’t mean that these people didn’t have any incentives. They still had plenty. It seems that for the Haudenosaunee culture and community that approval or appreciation was as potentially as powerful a motivator as fear or wealth is in ours, perhaps more so.

So, what do you do with the lazy? Give them a better motivation!

Work Or Die

There is another reason why some believe that others should earn their living, and that is the idea that otherwise they would be getting something for nothing. Not every pro-Capitalist subscribes to this view, some favour welfare to fill in the gaps, but many other pro-Capitalists would eliminate any welfare entirely.

It is as if - in such a philosophical framework - that the ethics of the poor learning a lesson about personal responsibility is greater than the ethics of society not letting them starve. But somehow an exception is made if they are born into wealth, if they are the children of the rich who inherited their parent’s fortunes, for some reason they are exempt from this ethical duty or consequence, but the children of the poor are not.

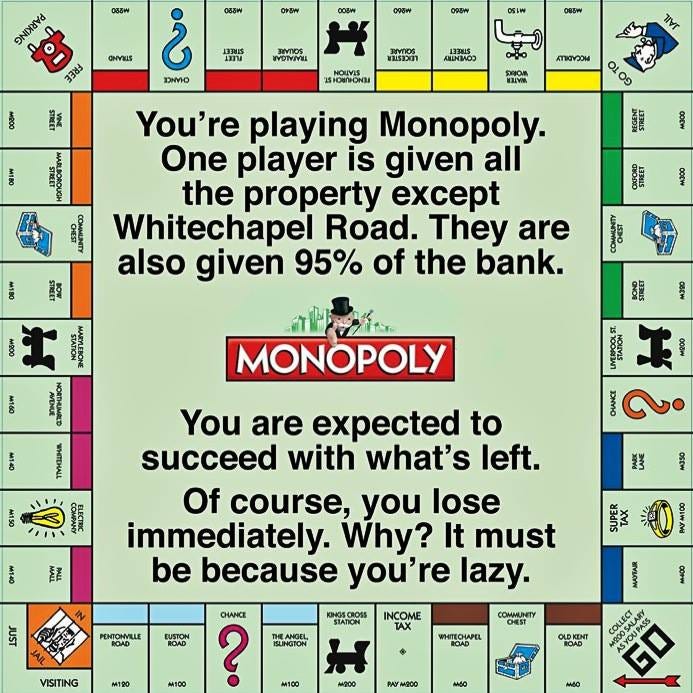

In the past I’ve shared my own beliefs on the subject by saying that I don’t believe the poor deserve artificial poverty, any more than I believe the rich deserve artificial wealth. But recently someone challenged me on my use of the word ‘artificial’ as if money was a naturally occurring resources that was somehow only obtainable by those who deserved it and was scarce to those who didn’t, and as if the whole economic system wasn’t a contrived 18th century invention.

In this same vein, some say the ‘lazy’ poor deserve their poverty, but also somehow believe the lazy rich somehow deserve their wealth. That it is right for the poor to starve or be homeless if they don’t work hard enough, but it would be wrong to take anything from the rich no-matter how they obtained it or what they are (or are not) doing with it. But, as pointed out, one may be better off through an accident of birth and another poorer for the same reason, which undermines the whole argument of people getting what they deserve based on their merits.

I come to these subjects with a different underlying assumption than these Über-Capitalists: I believe that people are more important than money, and that feeding people is a higher priority than someone making more money than they need. Maybe I’m simple minded, but it just seems that simple to me.

Lazy Under Socialism?

What happens to the lazy under Socialism is a great question I get asked often. I say it is great because it allows me to clear up some misunderstandings about laziness, about Socialism, and about how my views differ from those of authoritarians.

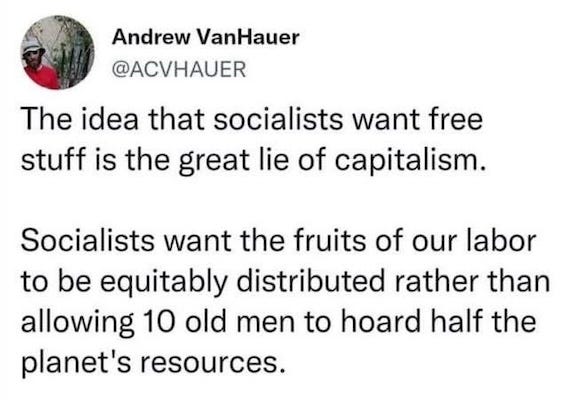

Some Marxists might answer this by quoting Lenin’s statement that ‘He who does not work shall not eat’ (paraphrasing Paul in Bible).9 However, I am not a Marxist or Leninist, and my own view is that food should not be a commodity, that we shouldn’t produce it for profit, and that as long as we have enough people to produce enough of it, we should share it according to people’s needs.

Since producing this food only requires about 1% of the population10 then I don’t see this being a problem unless over 99% of people suddenly ‘opt out’ of society. As humanity largely met their food needs for 99% of its existence before money or prisons or police existed, I don’t think we need any of those things to threaten people into helping or punishing them for not doing it. We can produce most of our comforts too with about a quarter of the workforce we have now (by eliminating excess, duplication and artificial scarcity and obsolescence).

Having said this, there will of course be social pressures and social incentives. Most children grow up wanting to do something, especially if given a chance to do something meaningful. Without having to worry about immediate needs as urgently there would be more opportunities for apprenticeships, mentorships, group work, making things of use, and seeing how fulfilling such work is, and how much it is appreciated by those who benefit from it.

Most people want to associate with other people, and working alongside them is a way to do this. Most people get bored with laziness, or they eventually feel guilty or awkward being around those they feel they are taking from without contributing. So there would be consequences, but the kind that come from excluding yourself from a major part of community life, and behaving in ways the community looks down upon. (Although, if you stopped working suddenly, in the sort term I imagine most people would just think you are sick or have a mental health issue, or just need some time to yourself, and ultimately would ask how they could help).

I’m personally far more concerned with a situation in which someone might not get enough food and be hungry, than with one in which someone might get free food and be lazy. I guess I’m more worried about suffering than fairness, especially if the cost of ensuring ‘fairness’ means potentially hurting someone to uphold the power and / or economic structure of the Capitalist system.

We Get Out What We Put In?

There are those who will point out the technological progress that our society has made in the last few hundred years and attribute it to Capitalism, and say this is what so many working so hard has enabled us to achieve. They wouldn’t want to go back to more humble times if it meant giving up such comforts, but – even if we are among those lucky enough to have them – those comforts are not evenly distributed throughout our society or outside of it. In the ‘developed’ world many of us enjoy a higher standard of living, but behind the scenes in the ‘third world’ many others who are paid much less (and sometimes not at all) are making our privileges possible.

Even in our ‘Western’ countries the upcoming generations are unlikely to have the same comforts older workers and the retired have been able to take for granted, and had available at their age. This isn’t because there is less money to go around, or because the population is greater, but because far less of the money goes to the middle or the bottom than it used to, and far far more goes to the top than ever before. The costs have been increasing greater than the wages have, just as the profits have risen exponentially, and a few have benefitted greatly from this arrangement, but the poorest have not been among them.

When you point this out some consider it envy, but I’m not convinced that it comes from jealousy over the wealthy having private jets, yachts, or mansions. It comes from poorer people wishing they too were in a position in which they didn’t have to worry about paying this weeks groceries or utility bills. The pro-Capitalist might argue that the wealthy worked hard for their wealth, and indeed some of them did, but it is doubtful they worked a million times harder than those in the world earning a dollar a day, or thousands of times harder than their employees.

It is true that some of the rich came from very humble beginnings, worked very hard, are very productive, make large sacrifices of their time for their work, and employ a large number of people making things we enjoy, even if we may often resent paying so much for them. Of course, they rarely made those products on their own; they usually required a large group working hard to bring them to market, and a small army to produce and service them. They have earnt a much smaller fraction for their hard work and sacrifices, in order to make the company successful, and if it had failed would usually pay a proportionally much higher price in their lives for the failure.

But the Capitalist continue to accrue wealth long after their original work. Money begets money through interest and investment, often without them doing any additional labor. This, we are told, is because they are ‘creating value’, as if they are creating it individually like the magic porridge pot, until we are all awash in a sea of oatmeal of their making, although – even then – the rest of us have to pay to access it.

I see them more as extractors of value — not creators of it — beyond their original contribution. The wealth of the world takes all of us to produce, but only a few to hoard. It would still be produced without the hoarders, but it would be more evenly distributed. Redistribution happens already, but it's almost all headed upwards instead of outwards.

The Iroquois were driven by contributing to something they collectively owned and shared. That's why Capitalism needs a much bigger carrot, it requires more drastic means to coerce workers into doing work they don't want to do, which largely benefits their bosses. I believe the evidence shows that humans are genuinely motivated when given autonomy and purpose, whereas Capitalist society actively disincentivises such qualities, and creates and rewards antisocial behaviours that often hurt others more than occasional laziness might.

Stolen Time, Stolen Life

If all this excess called ‘profit’ wasn't hoarded, think of how many hours we wouldn't have had to work, hours we could have spent with those we care for, or on ourselves. It's time we'll never get back, all to make those already rich even richer. Could a corporation making 10 billion in profit still employ you for 30 hours instead of 40, pay you the same, and still make 5 billion in profit? Yes, they could.11 The owners would still be rich, and you'd have more personal time and quality of life.

I'm not advocating against working at all, just for our access to food not being based on money, and for some of the gains in productivity and efficiency to lead to us working less, as so much of our labour unnecessarily goes toward making a few people wealthier. Beyond a million dollars, there isn't anything anyone needs that they can't get; beyond ten million, what does a person even want that they can't afford? Yet it seems their appetite for accumulation is insatiable, and with that extra money comes extra power and influence, which no society can afford the cost of.

But imagine if all wealth amassed beyond a certain point went to others, to workers who struggle with rent and bills, who could then enjoy the extra time away from work that is currently only going to make the rich richer, and imagine how much cheaper and more affordable the products would be if the owners didn’t expect such a large cut continually.

Or, alternatively we could just eliminate profit altogether, and produce for need instead. Such an idea is blasphemy to the theology of the pro-Capitalists, but we lived most of history without such a system, so it isn’t a new concept. That is my ideal.

I find it sad that so many people find it so hard to imagine a better world, one in which no one goes hungry or is homeless. and believe that this is the best we can hope for. It shows that pro-Capitalist propaganda has done its job well, but it has robbed so many from the real possibility of seeing the tried and successful alternatives.

There is a highly debated and often misattributed quote that, ‘it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than Capitalism’12, but I think it is best coupled with another one from Ursula K. Le Gunn that, ‘We live in Capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.’13

Without Capitalism people could work about 25% of what they do now and still have everything we need and most of what we want, but there would be no ultra-wealthy. Without Capitalism, we would all share more equally in the pie rather than 1% having 95% of it worldwide14, while we are lucky to feed on a few crumbs that drop from their table. Maybe then sometimes you’d feel like being lazy, but know that you could be, then after a good rest you could enjoy again working alongside your friends building a better world.

Any Relevant Questions? Such As -

Of course it may be the case that laziness doesn’t exist:

Laziness Does Not Exist: A Defense of the Exhausted, Exploited, and Overworked, Devon Price Ph.D., 2021.

Of course others question the whole need to work hard:

The Right to Be Lazy, Paul Lafargue, 1883.

In Praise of Idleness, Bertrand Russell, 1935.

And of course some see rest as a rebellious act:

Rest Is Resistance: Free yourself from grind culture and reclaim your life, Tricia Hersey, 2022.

A thirteenth-century estimate finds that whole peasant families did not put in more than 150 days per year on their land. Manorial records from fourteenth-century England indicate an extremely short working year (175 days) for servile labourers.

Although there always were some nomadic groups this was not the norm until the indigenous Americans were thrown off of their land and almost killed off.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_the_Iroquois

Cadwallader Colden, 1727.

Why The Cuckoo Is So Lazy - An Iroquois Legend.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_the_Iroquois

Ibid.

2 Thessalonians 3:10.

1.3% U.S.A. https://css.umich.edu/publications/factsheets/food/us-food-system-factsheet

Four day work weeks with reduced hours at the same pay, producing the same amount of work as previously, have been tried successfully. One example: https://research.reading.ac.uk/research-blog/2023/02/24/the-uks-four-day-working-week-pilot-was-a-success-heres-what-should-happen-next/

https://www.reddit.com/r/zizek/comments/w0u7ca/who_actually_said_its_easier_to_imagine_the_end/

https://www.ursulakleguin.com/nbf-medal

https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/worlds-top-1-own-more-wealth-95-humanity-shadow-global-oligarchy-hangs-over-un

Here's a fun challenge.

The next time you get your income, do nothing. Eat and sleep, but nothing else. How long can you do that for? Most people would struggle to manage 20min.

Then the goal posts move to doing nothing “productive”. But this is a capitalist framing. After the 20min, people will do something, and pretty much anything that gets done has some value for society.

And lastly, in a capitalist system, I prefer lazy people because they slow down capitalist accumulation of power.

Lots of good points. I tend to agree with Dr Price that laziness isn’t real - it’s a cultural judgement. Almost anything in life is “work” (in the sense of effort) and you literally can’t avoid it. Cooking, cleaning, bathing, walking, art, learning, conversations etc etc. “Work” and “job” are very different things (tho modern folks conflate them constantly). But effort is amoral. Stay at home moms work incredibly hard doing socially valuable work that isn’t a “job”. A weapons manufacturer CEO works hard doing less socially valuable work at his “job”.

I think people might be surprised to find that being a homeless addict is a lot of “work”. It doesn’t really fit the definition of “lazy”. Most people put up with jobs to meet their basic needs. Addicts’ have just developed a different kind of basic need and their reservoir of effort has been hijacked to meet it.

I do think that all life is effort - and humans innately seek to put their own effort into something meaningful. When they can’t (addiction, meaningless work etc) it generates sickness in society.